The German rescue lottery

The Federal Foreign Office wants to save 2640 Afghan activists from the Taliban. Those who wanted to be on the list needed luck and the right timing.

By Jürgen Dahlkamp, Matthias Gebauer and Roman Lehberger

By Jürgen Dahlkamp, Matthias Gebauer and Roman Lehberger

08.10.2021, 12.55 hrs – from DER SPIEGEL 41/2021

Source: DER SPIEGEL

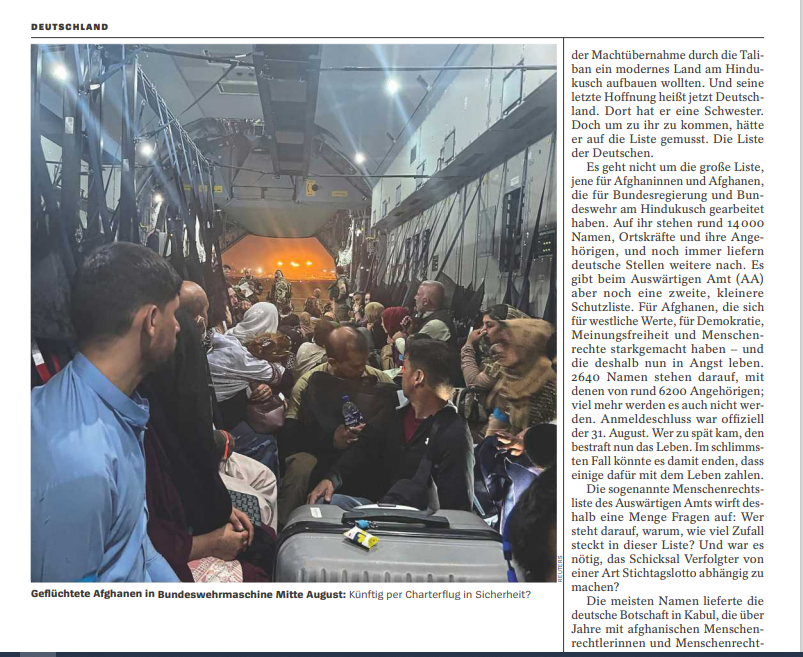

The photo is from a time when Mahdi M. still believed in his future in Afghanistan. And in a future for Afghanistan. That was in 2014, he was working as a director in the Afghan Ministry of Refugees, and in the picture he is standing just a metre away from the minister. There is also a picture with him at an international conference. Or articles with his picture that he wrote as a journalist. There is also a picture on the ID card of a university in Kabul where he gave lectures.

But now he has disappeared from the scene. In hiding in Kabul. The photo he sends via WhatsApp shows a blue pickup truck from which Taliban seem to be getting out: allegedly in front of his house. The Taliban had knocked on his family’s door to find him, he writes to SPIEGEL. Fortunately, he hid somewhere else in time.

Some of this can be verified, others not. One thing is clear: Mahdi M., 46, wants to get out of Afghanistan, like many of his compatriots who wanted to build a modern country in the Hindu Kush before the Taliban took over. And his last hope is now Germany. He has a sister there. But to get to her, he would have had to be on the list. The list of the Germans.

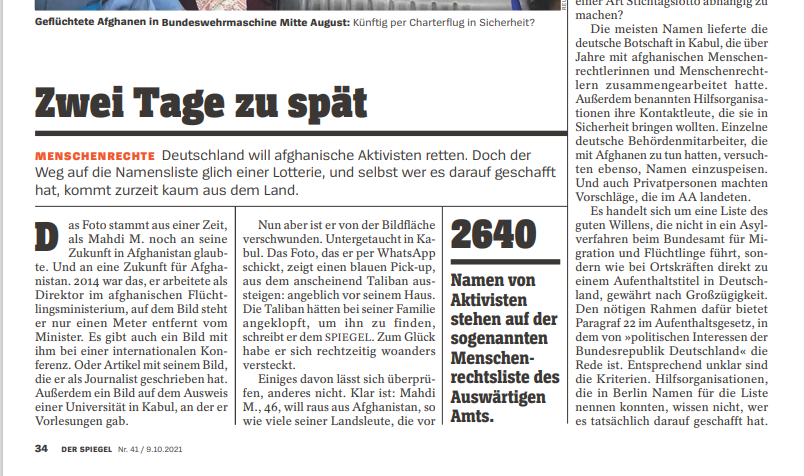

It’s not about the big list, the one for Afghans who worked for the Federal Government and the Bundeswehr in the Hindu Kush. There are about 14,000 names on it, local staff and their relatives, and German agencies are still supplying more. However, the Federal Foreign Office (AA) has a second, smaller protection list. For Afghans who have stood up for Western values, for democracy, freedom of opinion and human rights – and who therefore now live in fear. 2640 names are on it, with those of around 6200 relatives; there won’t be many more. The official registration deadline was 31 August. Those who came too late will now be punished by life. In the worst case, some could end up paying for it with their lives.

How much coincidence is there in the list?

The Foreign Office’s so-called human rights list therefore raises a lot of questions: Who is on it, why, how much coincidence is there in this list? And was it necessary to make the fate of persecuted people dependent on a kind of deadline lottery?

2640 names of activists are on the so-called human rights list of the Foreign Office.

Most of the names were supplied by the German embassy in Kabul, which had worked with Afghan human rights activists for years. In addition, aid organisations named their contacts who they wanted to bring to safety. Individual German officials who dealt with Afghans also tried to submit names. And private individuals also made suggestions that ended up in the AA.

It is a list of goodwill that does not lead to an asylum procedure at the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, but directly to a residence title in Germany, granted according to generosity, as in the case of local workers. The necessary framework for this is provided by Paragraph 22 in the Residence Act, which speaks of “political interests of the Federal Republic of Germany”. The criteria are correspondingly unclear. Aid organisations that were able to name names for the list in Berlin do not know who actually made it onto it. Even a government official who has campaigned on behalf of some Afghans cannot say today whether this has made any difference.

But even more than the secrecy, the deadline of 31 August makes people shake their heads. Reporters Without Borders, for example, reported 157 Afghan colleagues to the AA in time. In almost 100 cases, they did not make it. The editor of a magazine for women, whose work stands for everything that fits into the Taliban’s image of the enemy, is also affected; she did not send her desperate plea until 3 September. She could not have known that it was too late. Just as little as aid organisations could have guessed that 31 August – in the case of Reporters Without Borders, 1 September – would be retroactively declared the cut-off date by the federal government. With today’s knowledge, the preliminary examination of some applications at Reporters Without Borders therefore also took too long. “If we had known about the deadline, we would have worked 800 hours overtime instead of 600,” says Executive Director Christian Mihr.

Amnesty International was also caught cold. Until the end of August, the human rights organisation had only reported activists to the Foreign Office who could be brought to the airport quickly, i.e. people from Kabul. Those stuck in the provinces were supposed to wait for their chance. And therefore now have no chance, according to official German information. “We never thought there could be a cut-off date, otherwise we would have looked differently, more systematically,” says Amnesty International expert Julia Duchrow.

“The fact that the human rights list was simply closed without warning, even though thousands still have to be flown out, is proof of the government’s narrow-mindedness,” Wenzel Michalski, Germany director of Human Rights Watch, is also outraged. In fact, the Foreign Office has since added several dozen names to the list, most of which were informally submitted to the office by members of the Bundestag or journalists. However, the list is no longer open to the public for fear of being lost in the requests. Who, in very special exceptional cases and thanks to good connections, can still hope to be saved, therefore, remains nebulous.

It is also unclear whether activists had to have a connection to Germany to get on the list, for example as freelancers for German media. “Reporters Without Borders’ managing director Mihr says that more than half of the journalists they were able to promote to the list had no connection to Germany. On the other hand, an AA spokeswoman stressed at the government press conference that it was about people who had worked with Germans or had campaigned for “German causes”.

Even for the 2640 who made it onto the list, it will be hard enough to get out of Afghanistan. Although a charter plane from Islamabad, Pakistan, landed in Hanover on Thursday this week with 200 refugees, including some from the human rights list, they were received with packed lunches. They were received with packed lunches and are to be distributed among nine German states. “At the moment, however, the list only really helps those who have already made it out of Afghanistan themselves,” says Amnesty International expert Duchrow. Recently, the route to Pakistan and thus the most important escape route over land has been largely closed. Only last week, a bus belonging to Reporters Without Borders had to turn around at the border.

The reason: the Pakistanis spontaneously changed their entry regulations. Recently, the Foreign Office had solved the problem of many Afghans not having a passport with so-called verbal notes. In these, the Germans assured that Afghans from Pakistan would be allowed to fly on to the Federal Republic. Now, however, Pakistan has overturned the practice. No more entry without a passport.

Even with charter flights, it will probably take months before all those listed arrive.

That is why the crisis managers in Berlin are aiming for another solution. After seemingly endless rounds of planning, they are now confident that they will be able to fly Afghans from Kabul to Islamabad or the Gulf emirate of Qatar on charter flights in the coming weeks. The identity check at Kabul airport is to be done by a private security company, because there are currently no German diplomats in the country who could do it.

If the delicate mission succeeds – and that depends on the goodwill of the Taliban day by day – 200 people could be taken out on each flight, including a good 400 German citizens and their relatives who are still in Afghanistan and have priority. Even with charter flights, however, it would probably take months before all those listed – in the end probably around 25,000 local forces, activists and their relatives – would arrive in Germany.

The question remains whether threatened activists still have that much time. A whole team of reporters from the weekly magazine “Jade-Abresham Weekly”, in which Mahdi M., who had gone into hiding in Kabul, had also published political analyses, was able to make their way to the Pakistani border city of Quetta, according to their own information. In Quetta, too, however, Taliban were running through the streets everywhere. “It is very likely that they will find us; our lives are in danger,” one of them wrote to SPIEGEL this week. “Please help us and get us out of Pakistan. We urgently need your support.”

Add Comment