Writer: Yazdan Hatami, Afghan Freelance Journalist

Violence has been the major factor in involuntary population movements among Afghans. Since 2001, 5.9 million Afghans have either been displaced internally or have fled the country, primarily to Pakistan and Iran where they face an uncertain political situation.

Since 1970s, Pakistan has been hosting two million Afghan refugees, 600,000 of which are unregistered. Around 65% of the documented refugees is below the age of 25, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

Afghan refugees form three categories in Pakistan which include registered ones – known officially as Proof of Registration (PoR) cardholders; a group enrolled to UNHCR, and undocumented refugees.

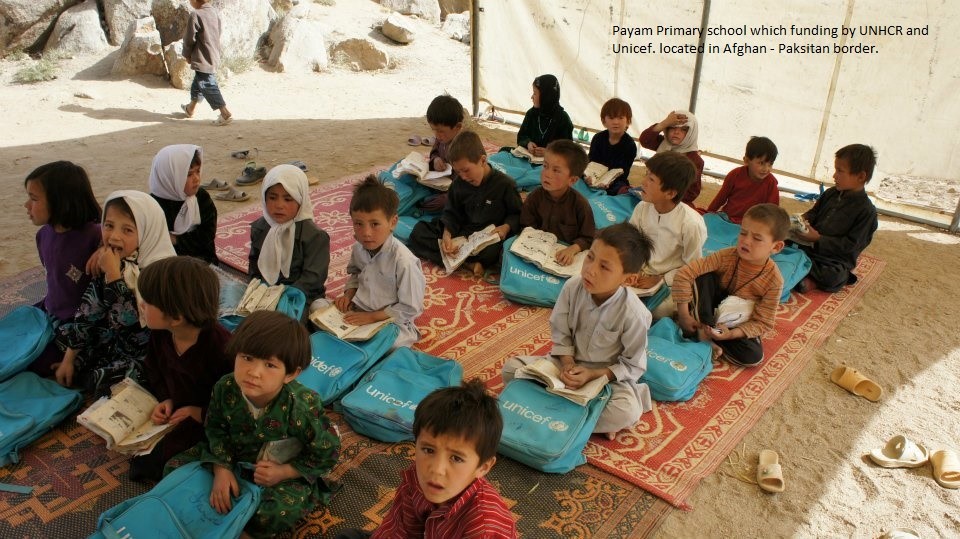

The United Nations estimates that almost 80 percent of school-age afghan refugees are currently not enrolled in and lack access to primary education. Given the Taliban takeover and recent developments in Afghanistan, education for Afghan teenagers in countries like Pakistan is more important than ever, especially for teenage girls.

Based on the UNHCR Education Strategy 2020-2022, it is estimated that in the last 40 years, the UNHCR inaugurated some 146 schools in 54 refugee villages (RVs) in urban and rural areas. These include 103 schools in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, 35 in Baluchistan and 8 in Panjab provinces. In total, the educational programs have benefited around 56,000 refugee children and provide salaries to 1,319 teachers and members of staff. Moreover, fifty-one Home Based Girl Schools (HBGS) have been set up in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Baluchistan for out-of-school girls who would otherwise not be allowed to attend regular school because of cultural reasons (UNHCR Strategy for 2020-2022).

Within the broader population of Afghan refugee children in Pakistan – particularly in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province – girls face additional obstacles in obtaining education. As of June 2021, it was estimated that out of the current 31,266 students studying at schools in the so-called ‘refugee villages’, only 35 percent were girls. In many areas, there are either no schools for girls or located too far from refugee housing, which leaves co-educational schools as the only available option – one that most conservative households choose not to avail (Evan Jones, 2022).

Within the broader population of Afghan refugee children in Pakistan – particularly in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province – girls face additional obstacles in obtaining education. As of June 2021, it was estimated that out of the current 31,266 students studying at schools in the so-called ‘refugee villages’, only 35 percent were girls. In many areas, there are either no schools for girls or located too far from refugee housing, which leaves co-educational schools as the only available option – one that most conservative households choose not to avail (Evan Jones, 2022).

Mrs. Shakila is an Afghan refugee, living in Quetta Baluchistan. She says her husband, who was a police officer in Uruzgan province of Afghanistan, was captured by Taliban gunman. One year after her husband’s capture, she, along with her seven children, crossed the Durand Line to flee the Taliban threat and enrolled to UNHCR in Pakistan. Out of her seven children, the elder of whom is 21 years old and the younger is seven, just three of them (two sons and one daughter) were admitted to government school but four other girls are not going to school. Pointing out the reason, she says, “When we came to Pakistan, we left everything behind in Afghanistan. In Pakistan, no one is supporting my family. My four daughters and I make livings via laundering and tailoring. Our life is really hard”. She adds that her all her daughters used to go to school in Afghanistan, but there in Pakistan, she cannot afford buying books or stationaries for her children or pay their tuition fees.

The southern Sindh province is home to 500,000 Afghan refugees, most of whom work as laborers or own small shops mainly in Pashtun-dominated areas. According to Sayed Mustafa, who founded a school for Afghan underage refugees in Sohrab Goth a Pashtun-dominated locality in Karachi’s capital city of Sindh in 2005, around 60% of the children residing in Sohrab Goth’s camps do not attend school. “This is because of a lack of educational facilities, poverty, as well as difference on the part of parents,” he told Anadolu Agency.

The southern Sindh province is home to 500,000 Afghan refugees, most of whom work as laborers or own small shops mainly in Pashtun-dominated areas. According to Sayed Mustafa, who founded a school for Afghan underage refugees in Sohrab Goth a Pashtun-dominated locality in Karachi’s capital city of Sindh in 2005, around 60% of the children residing in Sohrab Goth’s camps do not attend school. “This is because of a lack of educational facilities, poverty, as well as difference on the part of parents,” he told Anadolu Agency.

His high school charges a monthly fee ranging between 400 and 600 Pakistani rupees ($2.7-$4). Over 350 students, including 200 girls, study in the school mostly in junior classes. Female students are studying free of charge.

According to the UNHCR, more than 4.4 million refugees have been repatriated to Afghanistan since 2002, but many have returned to Pakistan due to ongoing violence, unemployment, and lack of education and medical facilities.

Only around half of Afghan refugees are registered, with the rest living without documents, mostly in northeastern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and southwestern Baluchistan provinces which border war-infested Afghanistan. For registered Afghan refugees, this status has importantly extended to them being able to access basic services, including primary education.

UNHCR Pakistan provides Afghan refugee students access to free Primary and (in some areas) secondary education through 153 schools, 48 satellites classes, 55 home-based girls schools and 13 early childhood education centers in refugee villages. Around 57,000 refugee children living in 54 refugee villages. Around 57.000 refugee children living in 54 refugee villages across Pakistan receive education through these interventions.

The UNHCR in Pakistan is seeking to overcome the challenges of refugee children in education sector through the following strategies, identified its refugee education strategy for (2020-2022):

1 Providing access to quality primary, secondary and tertiary education

2 Facilitating girls’ participation in educational centers

3 Including refugees within the public educational programs and systems

4 Strengthening the linkage to education pathways (UNHCR Strategy for 2020-2022)

Due to a multitude of barriers — which also pose challenges to underclass Pakistani school children — such as tuition costs, transportation expenses, the distance of schools from refugee housing, and outdated teaching practices amongst others, a large number of Afghan refugee children lack access to education.

According to Principle of Qayam School, a school founded in 2003 for Afghan refugee children in Hazara Town, a Hazara-dominated locality in Quetta, almost 12 schools with co-ed system are open in Borory Hazara Town area. The average 700 to 1000 students are studying in every school. Since August 2021 onward, enrollment of Afghan refugee children has increased on daily basis. According to him, despite other refugee communities, about 60% of students are enrolled in the schools are females. “This is because Hazara society is promoting and motiving girls to go to school both in Afghanistan and Pakistan,” he said.

His (middle) school charges a monthly tuition fee ranging between 600 and 1500 Pakistani rupees ($3.5 -$8), but some other schools charging monthly fee ranging (Grade 1-12) between 1000 and 2000 Pakistani rupees ($6-$12)

With the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, many children were also forced to abandon education so as to support their families in domestic labor. Loss of livelihoods within families also resulted in negative coping mechanisms such as an uptick in early marriages, particularly amongst girls.

Saleem Khan, chief commissioner for Afghan refugees, said the refugee children already have access to government schools across Pakistan, in addition to many skill development and scholarship programs for the youth.

“We are identifying the areas of higher demand in Afghanistan in order to train the (Afghan) youth. It will not only benefit them here, but they can also play a role in the development of their own country,” Khan told Anadolu Agency.

He cited long distance, poverty, and conservative beliefs regarding female education as key reasons for many children not to attend school.

Challenges for Afghan refugee children in Education Sector

In its latest report, the UNHCR says that currently only 32 percent of Afghan refugees live in 54 refugee villages across Pakistan, while 68 percent live in (semi-) urban settlement (Mapping of Education Facilities and Refugee Enrollment, 2017).

1. According to UNHCR 1.44 million registered afghan refugees and a further 600,000 unregistered afghan refugees are living in Pakistan. But no date has been complied or released by Pakistan authorities showing how many Afghan refugees immigrated to Pakistan after 15 August of 2021, fall of Ashraf Ghani’s government.

2. Over two million documented or undocumented Afghans refugee living here, but Pakistan has not been able to develop specific policies for Afghans living on it is soil in the past four decades (Pakistan Journal, 2021).

3. According to the Ministry of State and Border Religions, 32 percent of refugees live in camps and 68 percent in cities, villages etc. It is difficult for the Pakistani government to set up schools for them as they do not live in specific accommodation areas (Ahmad Ullah, 2020).

4. Another major challenge for Afghan children in education sector is that if they want to be admitted to state or private schools, the school authorities demand a birth certificate or Form B, but Afghan children do not have.

5. The major challenge is lack of resources and facilities in Pakistan for both Pakistani citizens and refugees. According to Ali-Ilan (a non-governmental organization) in Pakistan, nearly 25 million children are out of school (Pakistan Journal, 2021).

6. Economic and socio-culture factors are primarily responsible for the lack of school attendance by Afghan refugee children. The PoR card only protects Afghan refugees from being rejected without economic and social security. As a result, the refugees mostly work on the underpaid black markets and do not send their children to school, but are either married or work as child labor to ensure their financial survivor.

Pakistan is among the 30 countries in the world that offer unconditional birthright citizenship-meaning that a child born on its soil will automatically receive a passport. Section 4 of the Citizenship Art of 1959 confirms citizenship by birth. Every person born in Pakistan after the commencement of this act shall be a citizen of Pakistan. But this law never acts on Afghan refugee. Second or third generation of Afghan refugees, born on Pakistani soil, but not considered Pakistani citizens. Instead of the dark green Pakistani passports and national identity cards that citizens get, they’re assigned only Proof of Registration (PoR) cards, which entitle them to freedom of movement and temporary legal status in the country. Islamabad bars them from purchasing property, vehicles, and even SIM cards. They can’t attend public schools or universities. Hospitals often refuse to admit expectant Afghan mothers because they cannot issue birth certificates to the newborns. The refugees live each day with the looming threat of being deported to a country they have never set foot in.

Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan has suggested that he would reform the system. In September 2018, he announced that his government would grant citizenship to children of Afghan refugees.

And there was opposition within the general public too. On September 22, 2018, the local Express Tribune published a report quoting analysts and university professors in In Islamabad stating that issuing passports to Afghans born in Pakistan posed “threats to Pakistan nation security.” “Some of them fall trap of terrorist element,” the report stated. Or they may “get involved into anti-Pakistan activities”.

Two days after Khan made his statement, he backtracked, saying that his words were only meant to “stir debate” around the refugee crisis. It seems unlikely, then, that citizenship for Afghan born in Pakistan is in offing.

Data References:

1. Jahangir, Asif and Khan Furqan (2021). Pakistan Journal, Challegnges to Afghan Refugee Children’s in Paksitan. Volume 9, Number 3, Pages 7.

2. UNHCR (2019), Refugee education Strategy-Pakistan for 2020 -2022. Page 2-9.

3. https://www.trtworld.com/opinion/the-world-needs-to-step-up-support-for-afghan-refugee-education-in-pakistan-54845

4. https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/05/09/for-afghan-refugees-pakistan-is-a-nightmare-but-also-home/

5. https://tribune.com.pk/story/2306068/why-do-young-afghan-refugees-in-pakistan-lack-education-skills

6. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Pakistan_Map_RegistredREF_v02_April2021.pdf

7. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia-pacific/afghan-refugees-in-pakistan-pin-hopes-on-us-pullout/2215567

8. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia-pacific/why-do-young-afghan-refugees-in-pakistan-lack-education-skills/2279000

9. https://www.unhcr.org/pk/education

10. https://crisisresponse.iom.int/sites/default/files/appeal/pdf/2021_Pakistan_Crisis_Response_Plan_2020__2022.pdf

11. https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/costs/human/refugees/afghan

Add Comment